HISTORY OF THE DAYLE MCINTOSH CENTER

People often ask how the Dayle McIntosh Center for the Disabled (DMC) came to be. The answer is a simple one DMC founded its roots on the disability justice movement and officially opened its doors in 1977. Those who know DMC well, know this as a fact. However, what most people do not know is that all of DMC’s Founding Officers started their own paths of advocacy and activism as early as in the 1930s through the 1950s. This was long before DMC’s doors opened, and their individual fights for justice came because there was no legislation protecting the rights of people with disabilities during this time.

The time period before the Rehabilitation Act, and even the Americans with Disabilities Act was the educational ‘lived experiences training ground’ and often a battlefield to fight for equity around the access and inclusion of people with disabilities. All those dealing with day-to-day reality trying to navigate accessibility inconvenient truths, also were making changes along the way.

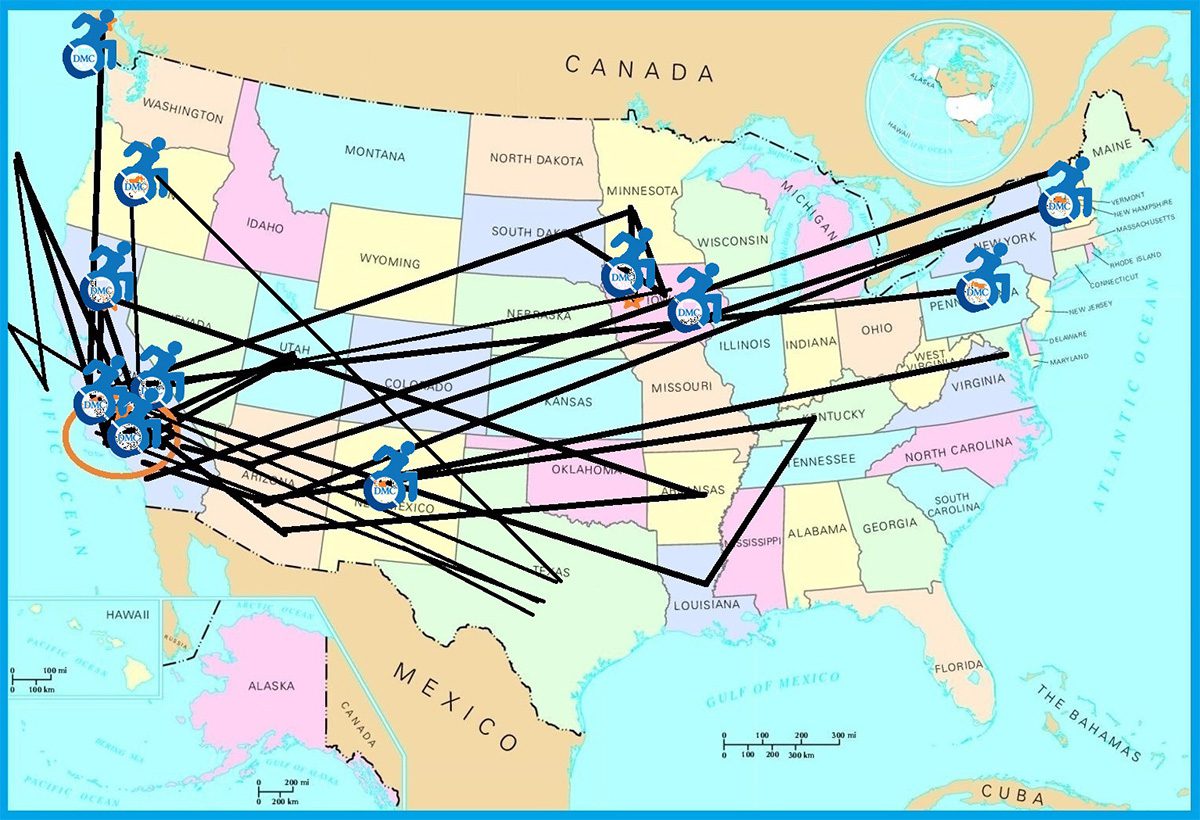

The system itself was in the early beginning stages of being able to meet the needs of the disabled. It was through all of the early advocacy and activism, change began to happen and it actually shaped what people know as DMC today. Our early pioneers had to build their own ramps of access (literally and figuratively), first traveling numerous directions across the United States and Canada to bring together eleven key individuals (leaders, activists, advocates and catalysts) with a handful of others in support to build bridges between local and state government support. The long, tough, and demanding road our founders traveled is something we deeply appreciate and respect.

Our Founder, Dayle McIntosh, the first Executive Director, Brenda Premo and many of our original Board of Directors were people with disabilities fighting for human rights through their own adversity, seeking justice, equity and the opportunity to live their fullest lives.

In the 1920s through the early 1950s, when most of our founders were born, it was not an easy time period. Some of our founding Board members were born during World War I, the Great Depression and World War II. As each member of our original DMC Dream Team eventually ended up in the State of California, these individuals arrived from different state systems, beliefs, conditions, family dynamic circumstances, training, and resources, and sometimes limitations based on those systems. Their “lived experiences” and hardships helped to facilitate conversations with non-disabled individuals and groups who could open doors, more aware of what was needed by the community.

Our founders became expert problem solvers overcoming the hurdles of many closed doors, minimal resources, restricted access to education due to grant limitations, and a lack of advanced healthcare research at the time to help people with rare disabilities. They also faced inadequate or non-existent access with very few (if any) wheelchair ramps to enter buildings, and repetitive rejection for assistance and employment. Our activists were born to fight for these things to exist, change, and grow for one common goal: To live independently.

DMC’s founders courageously spoke loud enough to be heard by government officials, other activist organizations, local, regional, state and grassroots non-profits and a variety of educational institutions so that change started to occur. Justifying reason, budget funding, with hard work invested producing enough data to make things happen became part of the fight — and they all had to do this long before Ed Roberts was born.

DMC’s founders courageously spoke loud enough to be heard by government officials, other activist organizations, local, regional, state and grassroots non-profits and a variety of educational institutions so that change started to occur. Justifying reason, budget funding, with hard work invested producing enough data to make things happen became part of the fight — and they all had to do this long before Ed Roberts was born.

Ed Roberts who is best known for being the early pioneer of the Independent Living Movement in the 1960s, brought great attention to numerous issues the disability community faced. He is celebrated for his efforts to bring the Independent Living Movement in motion for resolution in Berkley, California. He became the Director of California’s Rehabilitation Department, and helped develop a program of peer counseling and advocacy.

In 1973, the Rehabilitation Act was finally passed, and for the first time in history, civil rights of people with disabilities were protected by law. Getting to this monumental occasion was not a fix-all solution, though it was a welcomed start by many in the disability community. Recognizing the work still to be done, many small organizations joined forces. College campuses had united student protests and individually branched off to serving specific campus issues and building student centers. Individual activists stirred up attention with meetings and press conferences.

Many had to rally, sign petitions, write letters to government leaders, speak up at city council meetings, participate at national conferences with panels, write publications, and even sit on the lawn of the White House.

This was all before 1977. Our original activist founding officers took their own lived experiences, education, perseverance and timing – it was here the Dayle McIntosh Center came to be, from these roots.

PUBLIC VIEWED PHOTO CAPTION: This map shows the birthplace origins of each of our Founders and their journey through family moves, education and work locations before all ending up in Orange County, where they united to form The Dayle McIntosh Center for the Disabled (DMC) in 1977. However, all of their work started long before this date.

The long journey from our Founder, Executive Director and original Board’s birth places in Vancouver, Canada (Dayle McIntosh), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Greg Winterbottom), Albuquerque, New Mexico (Geno Vescovi), Ramsey, New Jersey (Ruth Finch Finley), Santa Paula, California (Tad Tanaka), Compton, California (Brenda Premo), Council Bluffs, Iowa (Paul Culton), Portland, Oregon (Peggy Hopkins Metro), Lakota, Iowa (Mick Spencer), and Californians Kay Goddard and Donald Nelson, all were fated to one day end up in one central place in Orange County, California. From education to employment to opportunities in the 1950s, 1960 and finally the 1970s, everyone ended up landing in Southern California.

HOW DID THEY ALL MEET?

Our known geographical hubs in Southern California are concentrated in Long Beach and Huntington Beach.

It is here, paths started to cross. While Dayle McIntosh was the fierce lone-warrior community activist pioneer paving the way for things to happen, Brenda Premo was “The Glue Hub.” In mainstream entertainment pop culture, we can equate her to the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon connection between all of DMC’s Original Dream Team. Both actively participated with many key organizations, conferences, rallies, government meetings and even through friends and the media where she appeared often, she connected all of our Board.

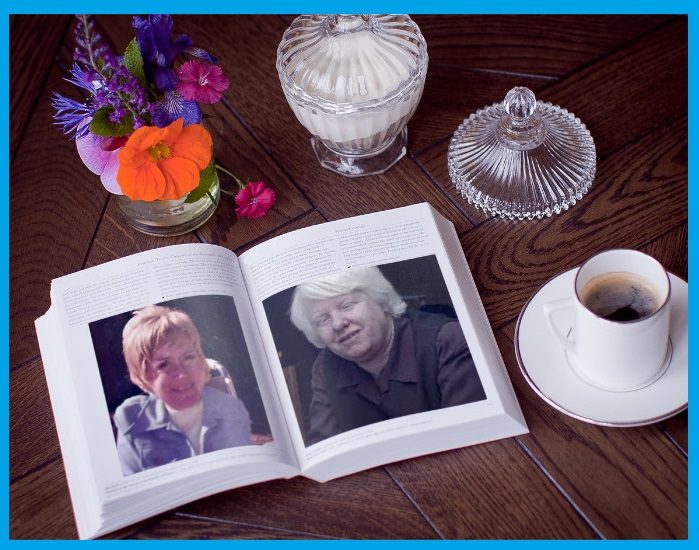

EARLY SEED BEGINNINGS: Dayle McIntosh & Brenda Premo

Born eleven years and 2,084 miles apart in North America– Dayle McIntosh and Brenda Premo were destined to eventually meet and create history. Canadian, Dayle McIntosh was independently doing her own activism and advocacy work in the United States, post-education in Southern California. McIntosh was already in the trenches with her own ‘pen mightier than the sword’ activism working as an editor for The Council Wheel in 1966-1967, an Official Publication of the Los Angeles Council for the Physically Handicapped (LACPH).

McIntosh was one of the earliest voices to push the boundaries, asking important questions and taking a stand when she saw injustice. She was already starting her community activism through writing and had attended Santa Monica College, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and California State University of Long Beach (CSULB). Brenda Premo was only fourteen years old at the time McIntosh was bringing important disability issues to light. However, Premo was about to get her spark of inspiration as she entered high school, later going onto college where her own activism would begin.

McIntosh started creating her own network along the way through conferences and meetings. One of these connections was Mick Spencer, who in the 1970s was active as founding officer and President of OC’s Chapter of California Association of the Physically Handicapped (CAPH). At that time, McIntosh was Editor of the OC Exchange for the organization. The chapter had a lot of members, but only very few, including McIntosh and Spencer, were actively advocating as the backbone of the organization itself. The two would eventually meet Premo and the three of them would end up collaborating to accomplish great things.

What McIntosh didn’t realize at the time, was she would eventually be connected by catalyst, educator and government representative Norma Gibbs, the Orange County Board of Supervisors and the Orange County Human Relations Commission to create what would be her own living legacy namesake of the Dayle McIntosh Center. Her joint work with CAPH would spread out like a spider web where they would meet all of the people who would hit the ground running to help form DMC. However, all of their paths were not scheduled to cross until a bit later.

Next: A Meeting of Two California Native Activists, Brenda Premo and Tad Tanaka:

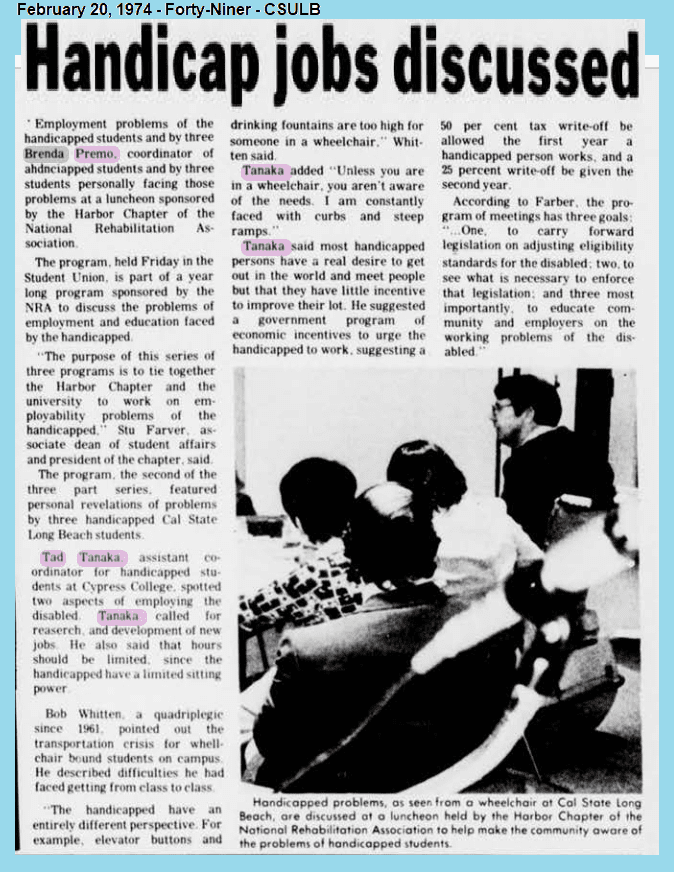

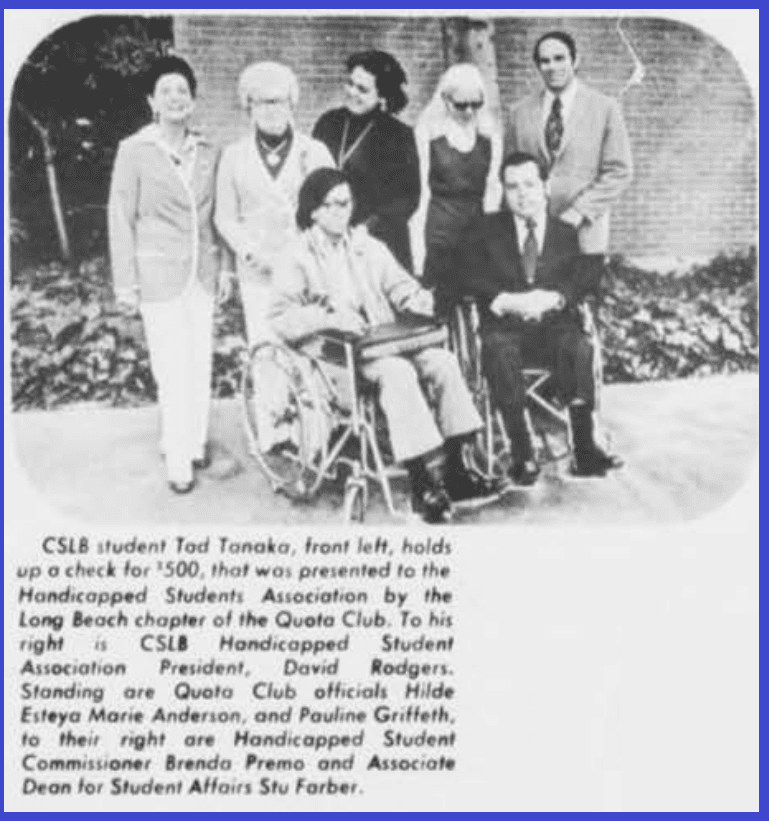

Dayle McIntosh was a student at California State University of Long Beach (CSULB), but her time on campus was far ahead of Premo’s. It was like two ships passing on different timelines. From 1972 to1976, Southern California native Premo was simultaneously pursuing her own education, and beginning her work experience journey all while being in the advocacy trenches. On campus is where she would meet up with fellow disabled student services activist cohort – the future original DMC Treasurer, Tad Tanaka. Tanaka was a Central California native who made his way to CSULB from Fresno. He had experienced his own challenges with accessibility in Fresno after an accident left him as a quadriplegic just after high school. He made his way to CSULB to further his education.

Together, they became activists-in-training as students, shaking up the campus, doing the hardest work through letters, rallies, discussions, meetings and creating student relations discussion topics for the disabled students. Encouraged by CSULB Dean of Students Kay Goddard, the Disabled Students Center was born from a ‘lunch bunch’ of people with disabilities. Goddard supported Premo to spearhead the center’s earliest beginnings. Here Premo and Tanaka both became active participants, not just working on campus through the Center, but outside of it joining the California Association of the Physically Handicapped (CAPH). These two were ‘on the ground’ answering the calls of the community and the campus, along with other nearby campuses who paid attention to the work they were both doing. As the campus leaders having the hard conversations, they brought about awareness to key issues, fiercely devoted to making a difference.

On CSULB’s Campus, something magical happened! A publication called “I AM” was born. It was first of the collaborative activism effort by pen between Brenda Premo and Tad Tanaka on campus. McIntosh had pioneered this effort earlier and elsewhere with other organizations, being the voice, being the pen, and being heard. Premo and Tanaka were following in her path unknowingly, doing what they had to do.

According to CSULB this newsletter started in September 1974 and was attributed to Handicapped Student Services. The newsletter changed the group name that it was attributed to in September 1978 to Disabled Student Services (DSS). Taking on many identity incarnations it went from being described as a newsletter, a magazine, and a newspaper. Most of the articles feature campus legislative and local updates to policies for disabled persons, campus updates on DSS policies and services, job opportunities, scholarships, technology, and other resources for disabled students.

Here, thanks to CSULB University Library, Special Collections and University Archives, Brenda and Tad’s contributions peppered within the 121 pages of “I AM” can be read here:

Read 121 Pages of “I AM” – Click HERE

Outside of this, Premo and Tanaka continued to make headlines together, often the subject of the campus paper The Forty-Niner.

Outside of this, Premo and Tanaka continued to make headlines together, often the subject of the campus paper The Forty-Niner.

Premo and Tanaka to shared space monthly in publications at CSULB and other places as they physically went out into the community to do their work.

Neither of them could be idle waiting for change, they fought for what they could at every level they could do individually with their respective roles, as well as together in collaboration to create necessary change.

Their advocacy journey was an outspoken one on all government and educational levels to overcome obstacles, prejudices with the hope to change the existing policies for fairness in housing, jobs and employment, health care, educational funding and independent research studies to attract mainstream public attention, and share struggles regarding day-to-day accessibility.

McIntosh, the founder, had already established a collaborative connection with Mick Spencer, who would later become a DMC Board Member At-Large. This partnership had its roots in their involvement with the California Association of the Physically Handicapped (CAPH). McIntosh’s efforts were focused on shaping impactful narratives concerning vital concerns within the disability community. Her approach involved various channels, including public speaking, writing, and community advocacy. During this period, she worked closely with Leona, Spencer’s wife, who held the position of CAPH Treasurer. Notably, McIntosh was also the Editor at the time.

It was within this context that McIntosh crossed paths with Brenda Premo and subsequently Greg Winterbottom, who later assumed the role of Chair/President. This connection was fostered as they collaborated with Premo during joint sessions involving the OC Board of Supervisors, Orange County Human Relations Commission, and the Government Officers of the City of Huntington Beach, including notable figures like Norma Gibbs and Ruth Finley (who was a City Council member at that time).

When Premo was a student learning American Sign Language (ASL) at Golden West College, DMC’s Future Original Board VP (Geno Vescovi) and Secretary (Paul Culton) were her ASL professors. Never forgetting what and from whom she learned – Premo believed in representation in the fiercest way. Because Culton was an ASL interpreter and a hearing person and Vescovi was a deaf person who spoke aloud orally – having them be on the board of directors together would enable Vescovi to interact collectively to exchange ideas with the rest of the board with additional access.

THE DREAM TEAM WEB CONTINUES:

Premo had met Gibbs through CSULB earlier when Gibbs was with Seal Beach City Council. Gibbs was friends and colleagues with Kay Goddard, one of DMC’s longest-standing Board members and the catalyst/supportive influencer for Premo and Tanaka’s on-campus initiation of work from Handicapped Student Services. Premo was later reintroduced in a different context to working with her, as Gibbs made her way to Huntington Beach government. It was here Gibbs’ work involved Premo with McIntosh to work with Spencer on the Spencer Ramps Project.

McIntosh’s introduction to Peggy Metro, a DMC Board Member at Large and Finance Chair, unfolded as she played a pivotal role in Peggy’s mother-in-law, Theresa Metro, assuming the presidency of the Beachwood CAPH Chapter. This endeavor aimed to empower Theresa Metro, a woman with disabilities. As fate intertwined, this interaction laid the foundation for a lasting connection between McIntosh and Peggy Metro.

Furthermore, the trajectory of their involvement led them to intersect with Brenda Premo, who took the reins of the Diablo CAPH Chapter. This juncture brought both Metros into the fold, marking the inception of a collaborative journey.

In the course of their engagement with CAPH conferences and affiliations with the United Way, McIntosh, Peggy Metro, and Brenda Premo encountered Donald A. Nelson. Donald A. Nelson, a DMC Board Member At-Large and Fundraising Chair, emerged as a significant presence, cementing their collective efforts towards common goals. As each attempted to make change together to lessen the struggle for future generations to come. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was not passed until 1990. It ensured the equal treatment and equal access of people with disabilities to employment opportunities and to public accommodations. However, our many of our founders felt this was still not enough and did their own advocacy work up until their deaths to pave the through their contributions to bring about awareness for real change.

Enter, OC Human Relations Commission and OC Board of Supervisors:

In 1976, Premo was one of the activists appointed to take on a project task force working with the Orange County Human Relations Commission. It was at this time Greg Winterbottom, was simultaneously fighting for parking for the disabled. This further fueled the demanding need to conduct a survey to determine the county’s own “needs assessment” for the disabled residents.

No State of California funds or Federal funds had been earmarked at that time for the opening of an Independent Living Center, however the needs were essential for a center to exist. All that needed to happen at this time was there needed to be tangible proof.

The Survey Birthing DMC:

The Orange County Human Relations Commission dedicated nine months to conducting a comprehensive study aimed at understanding the requirements of disabled citizens within OC. Collaboratively, the survey involved the efforts of Premo and Winterbottom, with the latter serving as the Executive Assistant to OC Board Supervisor Laurence Schmit at that time. This ‘needs assessment’ survey, sanctioned by the OC Board of Supervisors, was initiated to align with newly established state and federal regulations, designed to effectively address the requirements of the disability community.

During this period, McIntosh and Premo synergized their thoughts on conceptualizing the Independent Living Center (ILC). Drawing on her experiences, Premo brought her familiarity with Independent Living Centers, having previously visited the Berkeley IL Center in Northern California and the Westside IL Center in Los Angeles. She meticulously studied their infrastructure, services, and operational dynamics. These IL Centers had originated from a foundation of activism, advocacy, and a meticulous analysis of needs. This spark of inspiration ignited the subsequent course of action.

In August of 1977, the OC Board of Supervisors approved the project. There were plans for Dayle McIntosh to be the bookkeeper of the Independent Living Center. Sadly, McIntosh died August 5, 1977.

The Dayle McIntosh Center was backed by a $52,000 grant from the County Board of Supervisors, and a plan was made to open DMC’s doors in the City of Garden Grove. Still grief-stricken, Premo was gathering all of the key members she wanted to be on the Board of Directors as part of the founding officers of the non-profit organization.

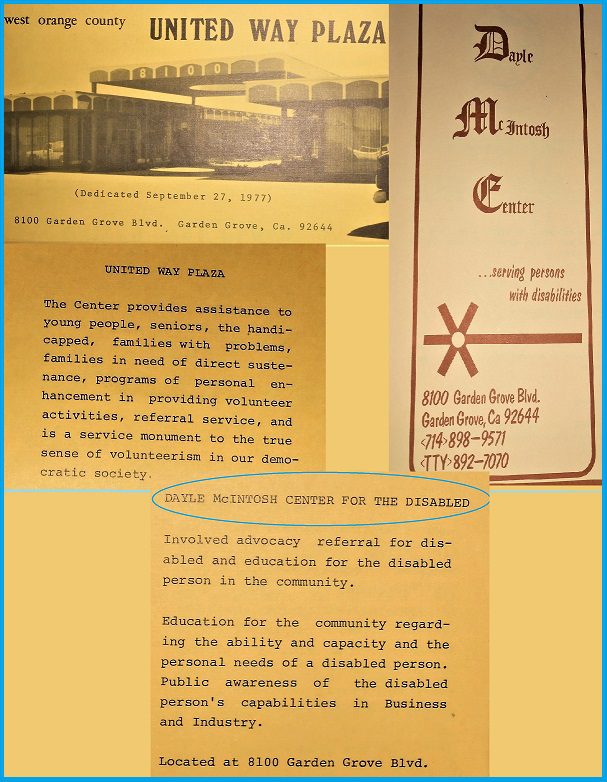

NEXT, DMC FOUND A FIRST HOME

United Way Plaza, a partnership location with unified missions brought us to where DMC would first call home. The official “dedication” of this center was on September 27, 1977. DMC had a soft grand opening of sorts as part of this dedication and was featured in the promotional materials, and DMC’s very first brochure was distributed to the community.

DMC was declared open October 24, 1977, reporting this to be the date to Orange County Chapter of CAPH for their Volume II, No. 9 October 1977 newsletter issue. The official opening day address would be 8100 Garden Grove Boulevard in the United Way Plaza of Garden Grove, California.

McIntosh was not able to see the sweet treat of Halloween night, October 31, 1977 when the funds actually landed in hand to declare November 1st, 1977 as DMC’s birthdate. Premo became DMC’s very first executive director, and collectively chose with the Board to name the organization after Dayle McIntosh.

At the time DMC was small but mighty, starting with just three full-time, four part-time employees and a volunteer Board of Directors. The organization had a lot of work to do to identify how DMC would show up, how word would get out and what the small team could do with what they had resource-wise, with where they were.

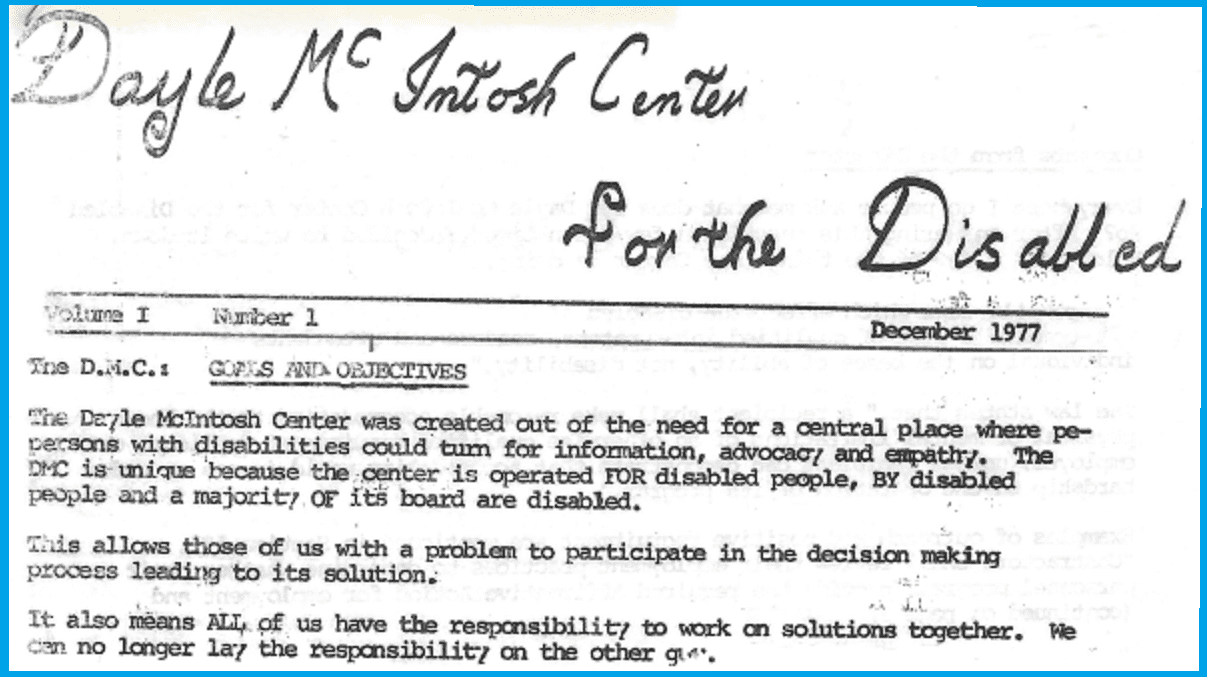

It was here the first DMC newsletter was born even though it did not yet have a name and there was no logo or brand. However, those things were not as important as “WHY” the Dayle McIntosh Center existed and it was all about being there for the community. The small team decided to ‘go for it’ and publish their first newsletter. It was in this newsletter DMC declared the official mission statement, which reads as follows….

DMC Goals and Objectives

The Dayle McIntosh Center was created out of the need for a central place where persons with disabilities could turn for information, advocacy and empathy. The DMC is unique because the center is operated FOR disabled people, BY disabled people and the majority of its board are disabled.

This allows those of us with a problem to participate in the decision-making process leading to its solution.

It also means ALL of us have the responsibility to work on solutions together. We can no longer lay the responsibility on the other guy.

The holidays were bittersweet, having lost Dayle McIntosh and jointly it was decided the only true way to honor naming the center after her as the team soldiered onward was to have an “official” open house with media in attendance. This is what DMC decided to do – have an Open House in December. At this time, DMC also put a general public call out to the disability community to help DMC name its newsletter, as well as cover general topics about accessibility. From here Team DMC would decide that come January 1978, it was a New Year, with named newsletter called NEW DIRECTIONS, with a new professional look to the newsletter.

The center did not officially get ‘incorporated’ until spring of 1978 (documents snail mailed, as there was no internet back then). Later the center would move to Anaheim, California and operate as a $1M Independent Living Center under both the Board’s and Premo’s leadership through both government and private funding. There were plans for DMC to grow even further, potentially to Irvine, CA – branching out with a move to Irvine, as proposed grant monies were available to begin moving DMC into other parts of the county. However, much like times change and government budgets get cut, DMC has ridden the rollercoaster of pivoting through time. Premo always believed private dollars and donors were essential to keep going and growing.

DMC is grateful for our original founding members. We acknowledge their struggle, fight and persistence in being brave enough to pursue the resources and bring together their common goals in order for our Independent Living Center to exist.

With no internet, no email, no cell phones, limited accessibility, a small staff and the rest of the world waking up to disability rights, we are extremely humbled and lucky to have such a talented, pioneering group of people who believed in making the world better for people with disabilities and older adults. Their work individually, and eventually together helped us become what we have become.

With the work of our original founders, their tireless service and commitment to helping to make things happen, we were able to open our own doors to provide “Access and equity by, and for, people with disabilities and older adults” at a time when it did not exist in Orange County.

DMC appreciates its humble beginnings. It is here we understand that as change occurs, with each new beginning which presents itself to grow, we reflect fondly upon our founders and say THANK YOU for being brave to do what you did. We will soldier onward in your honor remembering our roots of justice and movement forward.

To Learn More about the individual advocates and activists and their own stories – CLICK HERE